Andrew Cuomo's Housing Crisis

Andrew Cuomo isn't running for mayor to build housing for all New Yorkers. He's running for mayor to build power for the real estate state.

New York City’s persistent housing crisis is full of vexing contradictions. The city, which wields the most robust toolbox to protect tenants and prevent displacement in the United States, is also a global epicenter of capital and real estate. New York may be one of the few American cities where a sizable majority of the population rents, but it is also a city with a fiercely powerful real estate lobby, willing to spend nearly limitless sums to push back against even the most basic tenant protections. As a result, tenants, homeless New Yorkers, and even working-class homeowners are left to constantly fight back against the “real estate state”, a phrase that writer and urban planner Sam Stein uses to describe the all-encompassing influence real estate capital wields over our city, our politics, and the lives we are able to lead.1

Over the past 90 years, New York City’s Mayors have played a central role in shaping the housing market. Some mayors sought to weaken the power of the real estate state; in the 1930s, Fiorello LaGuardia crafted an innovative (and for many decades, well-run) public housing program that fused federal, city, and state funds in an attempt to eliminate slum districts across the city. The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) would go on to become the largest public housing authority in the nation by a large margin; the number of people living in NYCHA is approximately equivalent to the entire population of Orlando. In the 1950s, Mayor Robert Wagner Jr. tried to solve the joint problems of housing affordability and middle-class flight to the suburbs by helping the State Legislature to craft a large-scale middle-income rental and co-operative housing program now known as Mitchell-Lama. While Mitchell-Lama is not without its problems (the program was substantially weakened by an opt-out provision that allows units to go market-rate after their loan period ends), but it still provides tens of thousands of deeply affordable units for families across the city. During his two terms as Mayor, Bill deBlasio froze rents for rent stabilized tenants in 2015, 2016, and 2020, which helped protect New Yorkers from being priced out of their homes and neighborhoods.

Other mayors chose to reshape the housing market in ways that strengthened the real estate state, seeking to shift housing policy in subtle ways that disproportionately benefited landlords, the real estate lobby, and speculators. For example, in the 1970s and 1980s, Ed Koch used the J-51 tax break, initially designed to support property renovations in low-income housing, to encourage developers to convert affordable housing into higher-end units.2 This directly reduced the supply of naturally occurring affordable housing across the city, including single room occupancy (SRO) buildings, which often housed New Yorkers at risk of homelessness. In the 1990s, Rudy Giuliani created the tax lien sale, where the city sells the right to collect delinquent property taxes and water debt at a discount to predatory, private investors, who tack exorbitant fees, fines, and interest rates onto the debts families already owe, This speculative practice pushes vulnerable homeowners deeper into debt, and often leads to foreclosure.

Andrew Cuomo, the leading candidate for New York City Mayor in most major polls, is committed to strengthening the real estate state. As governor, he stalled for years on strengthening the state’s rent laws, allowing tens of thousands of units to exit rent stabilization. Unsurprisingly, the real estate state is returning the favor; landlords have given $2.5 million to a super PAC deceptively called “Housing for All” that’s spending its money blasting pro-Cuomo (and anti-Zohran Mamdani) ads across our TV screens.

Although he does have a 29-page housing plan on his website, it was written with assistance from ChatGPT, and mostly concerns how Cuomo would tweak around the edges of existing programs, such as expanding the city’s development rights transfer program and expediting housing review processes.

So what would housing actually look like if Cuomo was Mayor? Let’s read through the lines of his cryptic, typo-ridden, AI-written housing plan to find out.

Is Cuomo Actually Serious About Building Housing Supply?

Cuomo’s plans to build new housing in the city are, at best, half-assed. He claims he’ll build or preserve 500,000 units of housing over the next decade, most of which he wants to be affordable, but offers few solutions to actually get to that number. Sure, he supports advancing the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan, which could create almost 10,000 units of housing between West 40th Street, and West 23rd Street, but that plan is already in motion under the current administration. He seems supportive of office-to-residential conversions, but offers few solutions to actually incentivize these conversions beyond pushing the Department of Housing, Preservation and Development (HPD) to streamline its review of these projects, and making the Office Conversion Accelerator Program permanent.

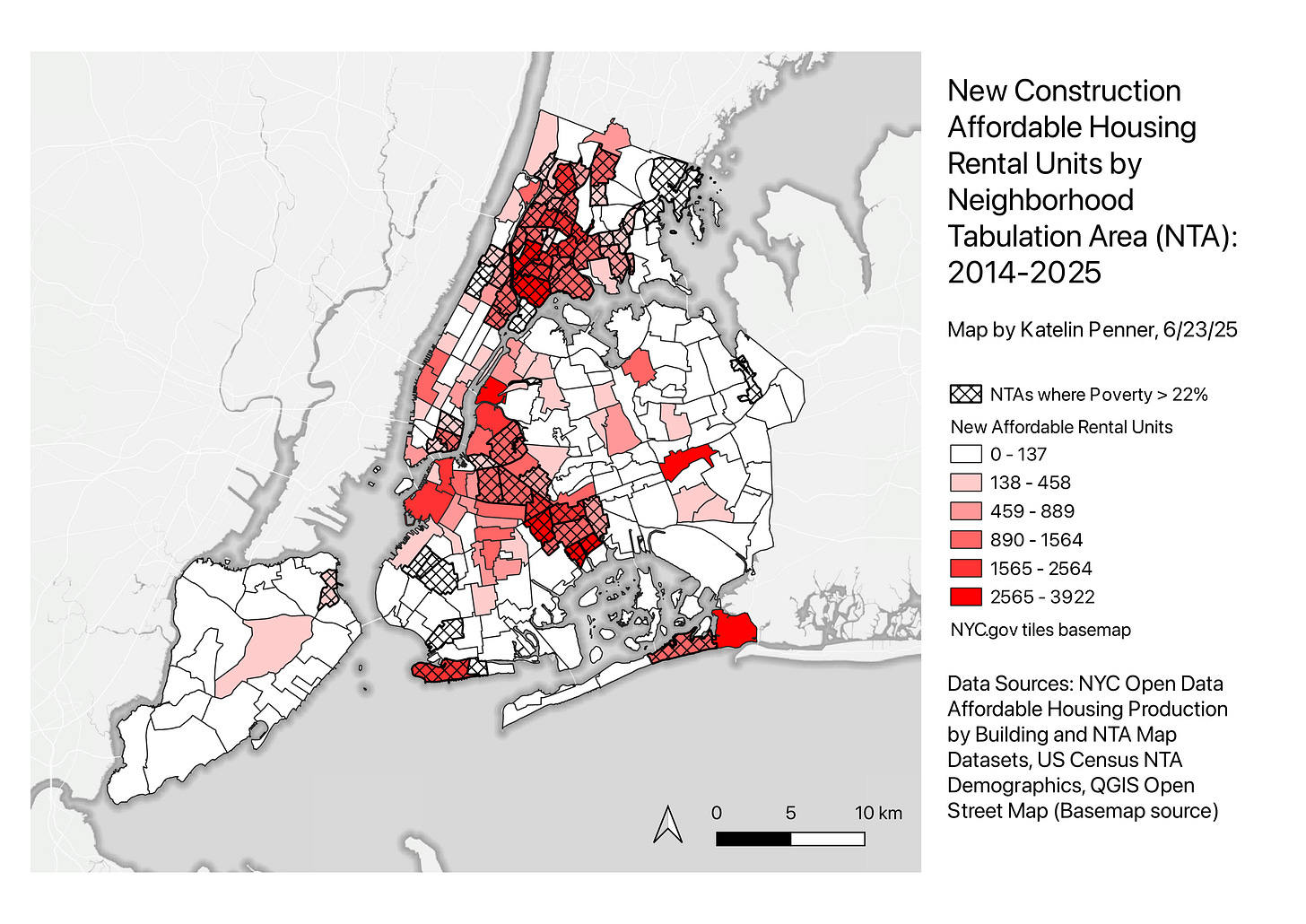

In many ways, Cuomo has more plans to not build housing than to actually build it. Buried in his unnecessarily verbose housing plan is a commitment to avoid pursuing “…further zoning changes in these low-density neighborhoods, at least until the impact of recent rezoning efforts are absorbed in these areas.” This commitment absolves certain (largely affluent and white) neighborhoods from building new (and perhaps more importantly, affordable) housing, while further concentrating housing production in a small handful of neighborhoods that have produced tens of thousands of units in the past decade and a half. This is particularly concerning for affordable housing, where projects have typically been concentrated in neighborhoods where poverty levels are higher than city averages, as opposed to being evenly distributed in communities across the city.

Furthermore, we can’t even count on Cuomo to push for new development in higher-density affluent neighborhoods. In a recent interview with the New York Times, Cuomo came out against the beleaguered (and as of today, formally extinct) Haven Green project, which would have provided 123 units of housing for homeless seniors on the site of the Elizabeth Street Garden, a small open space in NoLita. Admittedly, at face value, this situation may seem like something of a Sophie’s choice, forcing the city to choose between preserving green space and building desperately needed affordable housing. In Cuomo’s interview with the New York Times, he alluded to this apparent dynamic, saying: “In general, I think it’s a mistake to close gardens and green spaces. You know, quality of life. Find a vacant site that is not a green space. A city-owned site that really is suitable for affordable housing.”

But Cuomo, as the governor of the State for much of the period during which the Haven Green developers were in litigation with the garden, should know that this narrative intentionally obscures basic facts about the controversy. For one, the site, which has long been owned by the city, was never intended to be a green space in the first place. In the 1990s, at a time when the City was coming out of an economic recession, and still possessed a high volume of vacant land, the city began leasing the lot to Allan Reiver, a gallery owner who used the site to store sculptures. As the city’s stock of publicly-owned vacant land dwindled throughout the 90s and 2000s, then-mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed that the site be developed as part of a redevelopment plan in the early 2010s. In response, Reiver, who hoped to maintain his lease over the site and prevent new development, opened his space to the public in the hopes that park visitors would join him in the fight against this proposed housing development. He, of course, was right.

Cuomo also seems a bit too eager to jump at the idea that there are other, comparable city-owned sites where this project could have been developed. City owned land has become an increasingly rare resource for affordable housing development, as the city’s stock of vacant land gradually gets developed into affordable housing. This land is particularly rare in high-cost, affluent areas of New York, such as NoLita, where the Elizabeth Street Garden site is located. For years, garden enthusiasts like Robert DeNiro and Patti Smith (along with run-of-the-mill Lower Manhattanites) have claimed that they weren’t against new affordable housing, they were just opposed to it on the garden site. But the primary alternative site they propose, 388 Hudson Street, is also slated for a different affordable housing development. If the Haven Green project had been moved to the Hudson Street site, it would have lowered the reduced the already minimal number of affordable housing units the neighborhood was supposed to provide.3

While the Haven Green project is seemingly dead, Cuomo’s insistence at preserving the Elizabeth Street Garden shows just what kind of mayor he’ll be in land use fights — he’ll pursue a speculative, inequitable style of development much like that of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Like Bloomberg, Cuomo will stick up for NIMBYs in wealthy, mid-to-high density neighborhoods like parts of Brownstone Brooklyn and Manhattan, and homeowners in low-density neighborhoods.

So where will Cuomo build new housing?

With Cuomo’s reluctance to stand up for new development in rich neighborhoods, and his abject refusal to build new housing in low-density neighborhoods in mind, it feels increasingly likely that a Cuomo administration will recreate the same mistakes as the Bloomberg administration did on housing. Much like Cuomo, Bloomberg refused to build more in low-density neighborhoods, and largely avoided upzonings in white, affluent communities. Instead, the Bloomberg administration built two different types of housing in two different types of neighborhoods. As previously mentioned, affordable housing was concentrated largely in poor neighborhoods that had already produced massive amounts of subsidized housing over the past few decade, such as like East New York and the South Bronx. On the other hand, due to large scale rezonings, new, high-end, market rate housing was largely concentrated in neighborhoods actively undergoing gentrification, like Greenpoint/Williamsburg, Long Island City and Downtown Brooklyn.

The Bloomberg administration rarely pushed for affordable units in these upzonings, instead arguing that the construction of new rental units would reduce demand for lower-cost units with fewer amenities, helping to gradually drive down average rents. However, studies have shown that this phenomenon, often defined as “filtering”, is unlikely to happen in neighborhoods undergoing gentrification due to the extreme market pressures many of these neighborhoods were facing at the time.4 As more and more people are attracted to an area they previously wouldn’t have considered moving to, demand increases across the board, and landlords realize they can raise rents in low-amenity buildings, making even drastic increases in housing supply less likely to have a moderating effect on rents. This certainly was the case in Greenpoint/ Williamsburg, an area that Bloomberg infamously upzoned in the early aughts, housing stock grew by 23% in the years following the rezoning, but rents rose by an even more significant margin, rising by 80% in the first decade of the 21st century.5 Of course, this doesn’t mean that no new housing should be built in these neighborhoods — it merely means that relying on the market alone to provide “affordable” housing in gentrifying communities is a complete farce.

As Mayor, Cuomo will likely enrich his real estate donors by doubling down on Bloomberg’s approach, encouraging upzonings in gentrifying neighborhoods across the city. And while the City does have more tools at its disposal to encourage developers to construct affordable housing than it did during the Bloomberg administration, such as Universal Affordability Preference, which allows developers to obtain a 20% density bonus if all additional units built are affordable at an average of 60% of Area Median Income, these tools alone will not be enough to keep people from being displaced. And Cuomo, the largest beneficiary of real estate money out of all mayoral candidates, will not be brave enough to investigate new potential tools that could reduce the power of landlords and developers, like supporting efforts to create a state-level Social Housing Development Authority devoted to the production of mixed-income, mixed-use affordable housing.

Is Cuomo Serious About Ending Homelessness?

Cuomo doesn’t really cover homelessness in his Chat-GPT written housing plan; instead, he’s released a separate “Mental Health and Homelessness” plan where he seeks to cover the issue. His insistence upon linking homelessness and “mental health” is fundamentally problematic, because it feeds into the idea that all homeless individuals are either struggling with severe mental illness or substance abuse disorder, a misconception that drives stigma around homelessness. Furthermore, it means that Cuomo’s “solutions” to New York City’s homelessness crisis don’t address the needs of all New Yorkers; instead, they are largely focused on removing homelessness from the public eye.

To address the city’s homelessness crisis, Cuomo plans to build supportive housing, expand access to safe haven shelter beds, expand both residential and forensic psychiatric care facilities, and use the city’s power to involuntarily commit individuals to inpatient psychiatric facilities. Of his five main solutions, only two actually provide homeless individuals with permanent to semi-permanent housing: building supportive housing and expanding access to safe haven beds. The rest involve involuntarily committing homeless New Yorkers to understaffed, overcrowded psychiatric facilities where they may experience more trauma, and are likely given few resources to avoid homelessness upon their discharge. Furthermore, there are serious civil rights issues regarding long-term, forced hospitalization, particularly when patients are forced to take medications or undergo medical procedures that may have serious side effects, such as electro-convulsive therapy.

There are alternative solutions to involuntary commitment, however, including Housing First, an evidence-based policy that involves providing homeless individuals with housing without requiring that they abstain from substance use, enter the shelter system, or meet any other restrictive requirements. The program’s ethos revolves around the idea that for many homeless people, it is easier to address mental health issues or substance use challenges after they have accessed stable housing. It has a higher success rate than traditional programs serving homeless populations — between 70-90% of Housing First participants remain stably housed two to three years after receiving services, compared to 30-50% of participants in traditional programs. Despite this, Andrew Cuomo does not see the policy as a major part of his homelessness plan, arguing that “…Housing First is not a silver bullet”. Instead, under a Cuomo administration, more and more of our homeless neighbors are likely to face long-term, involuntary psychiatric commitments.

A Note On Cuomo’s Record on Homelessness

It’s a bit ironic that Cuomo seems very concerned with the threat that street homelessness poses to New Yorkers’ safety; his record shows that he is actually to blame for much of the city’s homelessness crisis. In 2011, Cuomo cut off state funding in 2011 for a rental voucher program known as Advantage, which led then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg to eliminate the program all together. Advantage, which Bloomberg started in 2007, offered 15,000 New Yorkers rent subsidies for up to two years to help people move out of shelters. The program was imperfect; Advantage was justly criticized it for its short time limit and work requirement for voucher holders, but most advocates argued that they wanted to see the program improved, not eliminated all together.

Unsurprisingly, getting rid of the program had an immediate, negative effect on homeless families. Between 2011, when the program was terminated, and 2013, the shelter population in the city skyrocketed by 35%. As a result, when deBlasio came into office in 2013, he gradually began to recreate a voucher program, building what is now known as CityFHEPS. As Governor, Cuomo denied multiple requests to help fund the CityFHEPS program, despite its growing cost to the city. While Cuomo does commit to funding CityFHEPS in his housing plan, he does cast doubt on the city’s financial ability to continue supporting the program, raising concerns about the future of this vital voucher program, which currently supports over 50,000 New Yorkers.

Is Cuomo Serious About Protecting Tenants and Vulnerable Homeowners?

New York City is unique for its fairly widespread tenant protection programs, which are an absolute necessity in such a high cost municipality. The city’s long-standing rent stabilization program, which is largely controlled by the State Legislature, is perhaps the most important protection available to tenants in the five boroughs. Tenants living in rent-stabilized apartments, which typically include units built before 1974, receive some protections, including limits on how much one’s landlord can increase rent each year, and a guaranteed right to renew one’s lease. The limit on how much a landlord can increase a stabilized tenant’s rent each year is determined by the Rent Guidelines Board, a nine-member city government agency that analyzes the average cost of living for tenants and the average cost of operations for landlords to establish a rent increase that is supposedly fair to both parties. For many New Yorkers, rent stabilization has acted as a powerful anti-displacement tool, helping keep families in their communities amidst ongoing gentrification. But Andrew Cuomo, who would appoint the members of the Rent Guidelines Board as mayor, certainly doesn’t see the policy in this light, posing a serious threat to stabilized tenants.

In his AI-written housing plan, Cuomo seeks to brand himself as a champion for tenant protections. claiming he had a central role in expanding the state’s rent stabilization law in 2011, 2015, and 2019. This, of course, is a lie — Cuomo was a primary obstacle to passing tenant protections through the State Legislature for most of his first two terms.

For years, Cuomo allied himself with the Independent Democratic Conference, a group of rogue Democrats who caucused with the Republicans in exchange for illegal stipends and committee chairmanships, to box the Democratic Party out of the majority in the State Senate. This allowed Cuomo (and the IDC) to block progressive legislation, such as strengthened rent laws, without having to directly say that he opposed them. Of course, this kept Cuomo’s real estate donors happy — it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Cuomo, a booster of the real estate state, received over 12.3 million dollars in campaign contributions from the real estate industry while serving as governor.

For years, Cuomo preserved a number of loopholes that allowed apartments to deregulate and exit rent stabilization. In both 2011 and 2015, years when Cuomo claimed that he “strengthened” rent stabilization, vacancy bonuses, which allowed landlords to increase rents in stabilized units by up to 20 percent when tenants moved out, and high-rent decontrol, which allowed landlords to pull units above a specific rent threshold from rent stabilization once the unit was vacated, remained part of the program. As a result, the city lost tens of thousands of rent stabilized units between 2011, when Cuomo was elected Governor, and 2019, when the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act was passed (much to Cuomo’s chagrin).

It is important to note that Cuomo was Governor when the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, which meaningfully strengthened rent stabilization in New York City by closing the vacancy bonus and high-rent decontrol loopholes and clamping down on landlords’ ability to permanently raise rents for making renovations. But he shouldn’t get any credit for getting it over the finish line. That credit belongs to both an increasingly pro-tenant state legislature (due in large part to the defeat of the IDC), and a mass movement of tenants, who came up to the State Capitol by the thousands to demand stronger tenant protections. With that in mind, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Cuomo has tried to distance himself from the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, arguing in his housing plan that the bill “had unintended consequences” that prevent landlords from raising rents. And it should be even less surprising that Cuomo, a candidate who has sold himself out to the real estate state, is now the only major candidate in the Democratic Primary who has refused to commit to freezing the rent for stabilized tenants this upcoming year.

“Andrew Cuomo was for at least two cycles, the biggest obstacle to strengthening and expanding rent stabilization. We only got it done when the newly-empowered legislature agreed to do it without him. I'm glad that he signed the bill, but he had nothing to do with crafting the legislation. He fought it every step of the way." - Cea Weaver, Housing Justice for All

Throughout his spotty housing platform, Cuomo also claims he’ll strengthen enforcement of rent stabilization laws and Good Cause Eviction ( a bill he notably fought back against while governor). But his own record suggests that he is not equipped to fully enforce these laws. In 2012, Cuomo formed a Tenant Protection Unit within the State Department of Homes and Community Renewal (DHCR) to investigate landlord fraud, discrimination, and illegal deregulation of stabilized units, but the division was notoriously ineffective. As Charlie Dulik noted in a recent piece in Hell Gate, studies show that DHCR took an average of 10 months (almost the length of a one-year lease!) to resolve a tenant's complaints. Perhaps more concerningly, 15 percent of all complaints weren't even assigned to an investigator within two years, leaving many tenants without help to fight back against landlord harassment or fraud. Of course, this can partially be attributed to Cuomo refusing to give his Tenant Protection Unit the resources it needed to operate successfully — the taskforce only had 25 staffers to investigate landlord fraud across the entire state.

Follow the Money

Cuomo’s housing policies leave a lot to be desired. His commitments to build new housing are decidedly weak and play into long-term, inequitable patterns of development. His proposals to address homelessness are likely to increase the stigmatization of homelessness while offering few people permanent housing, while his commitment to policies that protect tenants are extremely weak.

At this point, it’s clear what’s driving Cuomo to craft such bad housing policy — the real estate moguls who are bank rolling his campaign. Housing for All, a deceptively named $2.5 million dollar super PAC supporting Cuomo, is primarily funded by the New York Apartment Association, an organization that lobbies city government and the Rent Guidelines Board on behalf of landlords. The organization’s CEO, Kenny Burgos, applauded Cuomo’s claim that, if elected, he would "blow up the Department of Housing, Preservation, and Development (HPD)” at the first debate, arguing that “(HPD) is bringing on layers upon layers of violations to owners”. To make matters worse, many of Cuomo’s biggest landlord donors, such as Peter Fine and Douglas Eisenberg, are actively being sued over conditions in their buildings by the Department of Housing, Preservation, and Development (HPD), raising questions about whether these donations are an attempt to curry favor with Cuomo, and weaken HPD’s ability to enforce housing code violations.

Despite the vagueness of Cuomo’s policy proposals, one thing remains crystal clear. Andrew Cuomo’s housing plans are designed to benefit (and strengthen) the real estate state, not the needs of every day New Yorkers who can’t find an apartment they can afford to rent. If we elect Cuomo, we can expect years of stalled progress on building new homes across the city, ending homelessness, and actually enforcing our city’s housing laws. If we choose a different path, maybe (just maybe) we can finally win a city where there is actually housing for all.

Polls are open today from 6am to 9pm. You can find your polling site here: https://findmypollsite.vote.nyc/

Stein, Samuel. Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (London, UK: Verso, 2019), 3-4.

Holtzman, Benjamin. The Long Crisis: New York City and the Path to Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press, USA, 2021, 179-180.

In the garden deal that was announced yesterday, the units proposed for Haven Green were instead moved to a private development on the Bowery, where an upzoning will enable these units to be built along with an otherwise market rate building.

Liu, Liyi, Doug McManus, and Elias Yannopoulos. "Geographic and temporal variation in housing filtering rates." Regional Science and Urban Economics 93 (2022): 2-3.

Angotti, Thomas, Philip DePaolo, and Sylvia Morse, eds. Zoned Out!: Race, Displacement, and City Planning in New York City. Urban Research (UR), 2017: pg 86.